These are difficult texts for me to comment on. One defining aspect of modernism was the widespread feeling that a rapidly changing world demanded a search for new forms of literary expression. The formal inventiveness that we see here is one aspect of that search. Although the presentation of "It's Raining" is meant to challenge how we visually receive poetry, the text is much more concerned with suggesting aural impressions: "its raining womens voices" ... "a universe of auricular cities" ... "listen to the rain" ... "an ancient music" ... "listen to the fetters". The poem conjures up the idea of rain as both a visual and aural experience, and links them with memories and regrets; the rain seems to be a spiritual deluge which emanates from the past. I'm particularly struck by that phrase "a universe of auricular cities," which suggests a vast, intricate sensory environment, a reality large enough to get lost in. If I'm right in thinking that the poem has to do with memory, or "marvelous encounters of my life," does this suggest that the kingdom of memory represents an escape from the physical realities of war? Perhaps, but that escape is double-edged, even another kind of prison, because the memories seem to be so melancholy. The rain is a literal thing, falling from "clouds," but it is also an "ancient music" wept by "regret and disdain." It's a spiritual and physical force, and it binds both the mind ("high") and the body ("low"). The image I get is of a soldier in the trenches, soaked to the bone, imprisoned in both the physical present and a cage of memories.

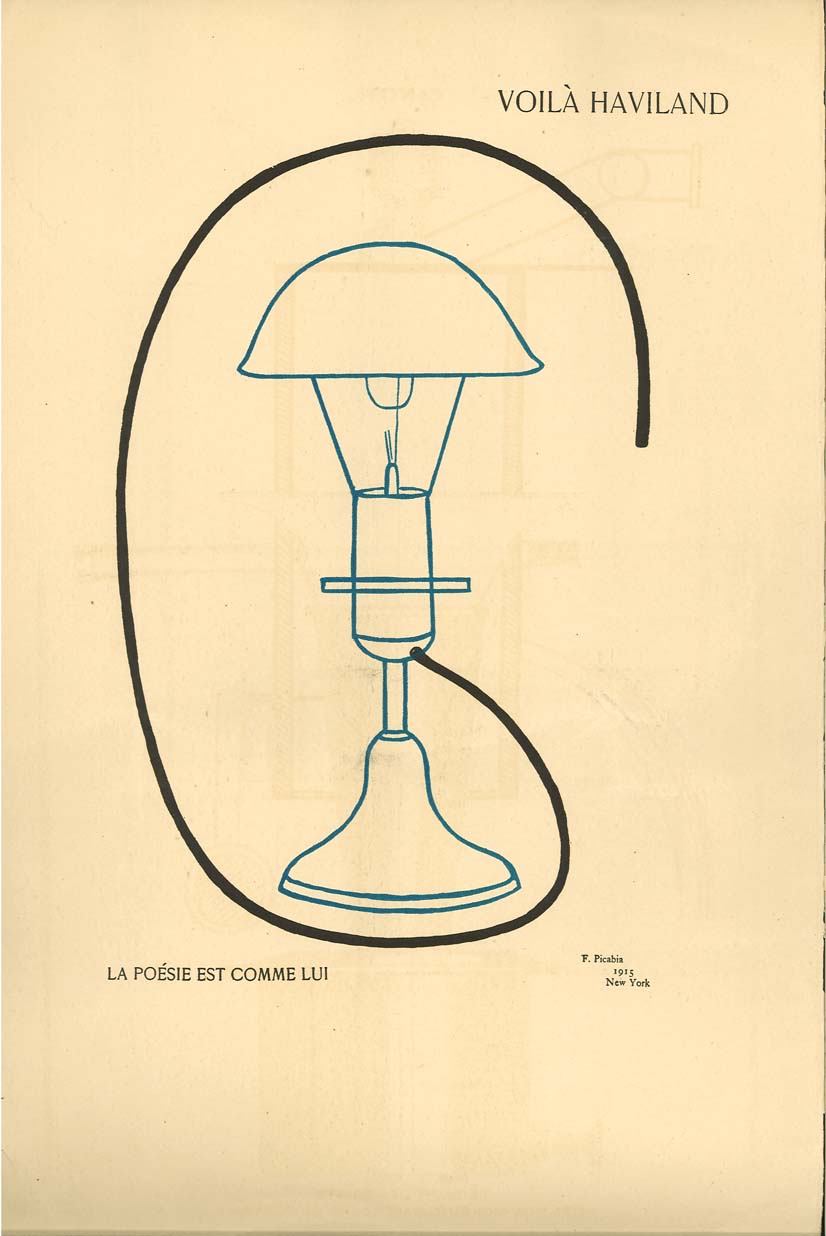

Much of De Zayas' piece in the Stieglitz magazine strikes me as incomprehensible, but I am intrigued by the phrase "He married Man to Machinery and he obtained issue." De Zayas is talking about photography, but there may be other applications to be found there. The phrase aptly, for instance, describes a page depicting some kind of mechanical object with the heading, in French, "Portrait of a young American girl in the state of nudity." The other images (also by Picabia, praised by De Zaya as having "married America like a man who is not afraid of consequences") have similarly ironic captions: "Here, this here is Stieglitz; faith and love." "The holy of holies; it's me that is in this picture." "I have seen and it is of you." "Poetry is like this." (I was never a very good French student. Others may be able to translate better than I.) This expresses a pervasive fear of modernism: faith, poetry, and the human being are all equated with quasi-mechanical forms. But these forms remain elegant and pleasing to the eye. The are aesthetic impressions of mechanization, rather than depictions of any kind of real functionality. For all De Zayas' complaints that American art is cold, artificial, methodical reather than organic, Picabia's visual representations are alive, irrational, creative, surprising. That said, the images of "Stieglitz," "me," and "you," are much more interesting and varied than the image of the "young American girl." So although the artistry displayed in these drawing seems to undercut its message about the mechanization of the human, the message of European elitism remains intact.