Je suis venu sur les rivages

Submitted by Victoria McGouran on Wed, 03/06/2013 - 17:33

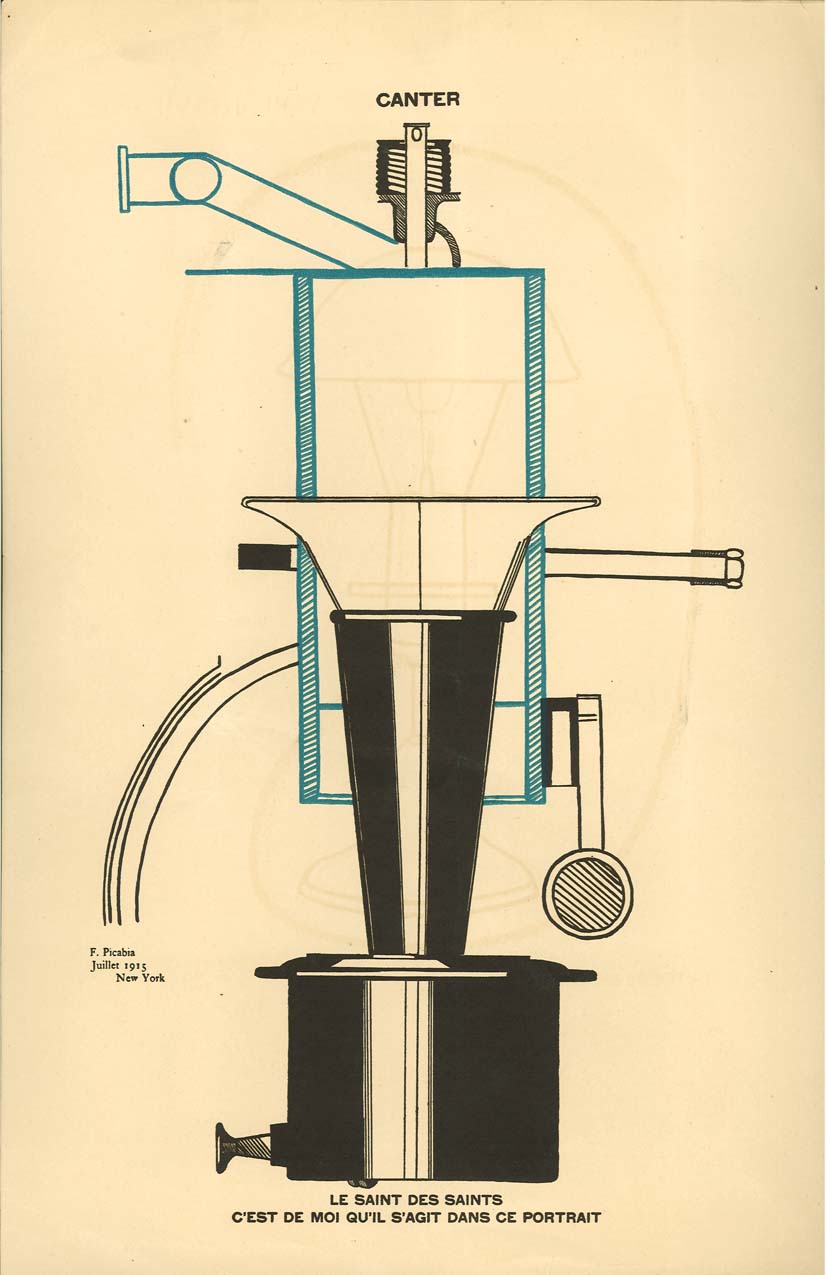

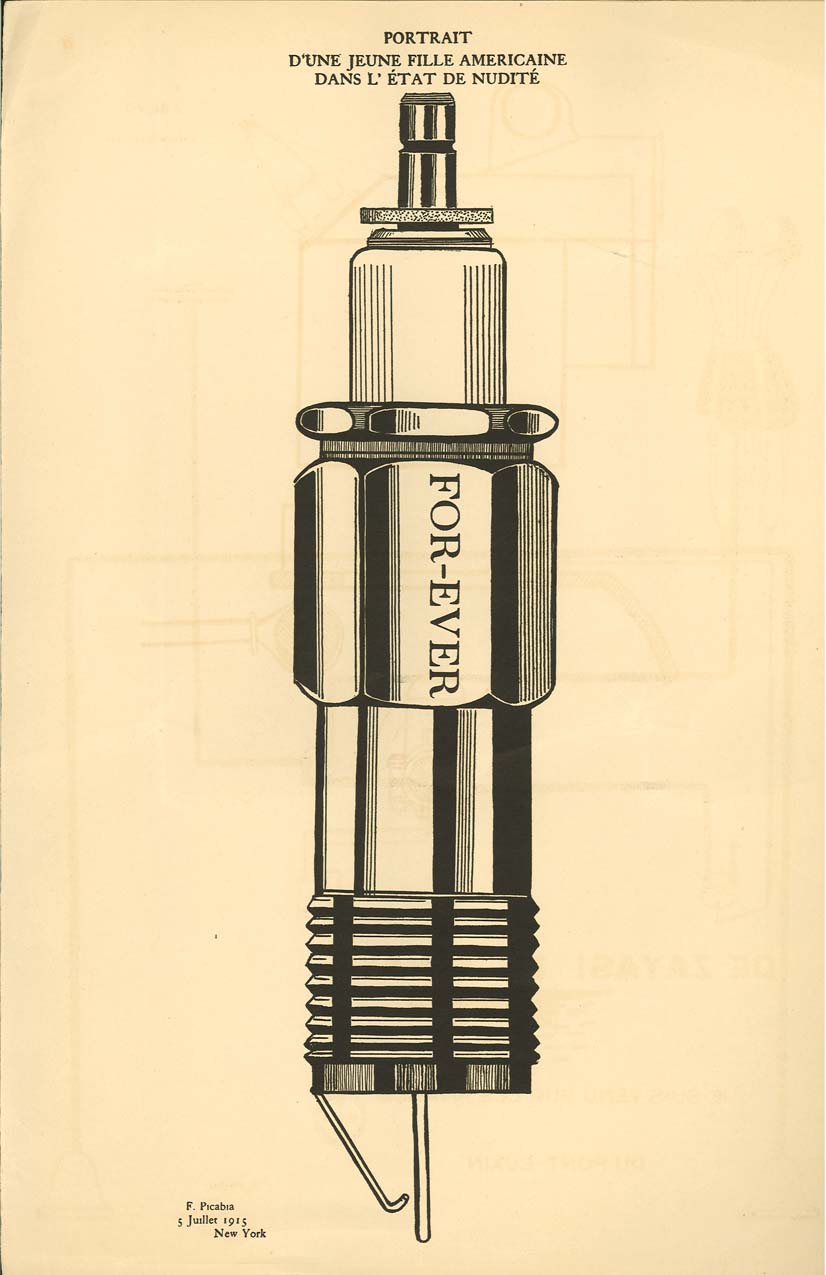

The image I chose to examine for this post was created in 1915 for Alfred Stieglitz's Dada magazine, 291, by a French artist named Francis Picabia. Picabia was associated with Cubism, Abstract art, Surrealism and Dada, which lends a unique look to his artwork. Picabia was also a member of a group of artists who were retroactively labeled, 'New York Dada'. The New York Dada group arose almost independently of the movement in Europe and their works grew up around Alfred Stieglitz's art gallery which was named 291. The Dada movement arose as an artistic revolt against war, sexism and racism, however, the New York Dada movement seems to have a more oblique purpose. The New York artists were not associated with the anti-war works of their European counterparts, however, many of them were from Europe and had moved to New York to escape the war. With that in consideration, much of their art could almost be considered protest art, but not in the same sense as the European Dadaists.

All that said, this issue of 291 was primarily constructed by Picabia as a visual salute to the creators of the magazine. The image above was called De Zayas! De Zayas! and was a metaphorical picture of Marius de Zayas, one of the primary creators of 291, re-imagined as some kind of mechanical being. However, the text in the image reads "je suis venu sur les rivages, du pont - euxin" which roughly translates to "I came on shore, Bridge - Black Sea". This line is very confusing in context with the image and it's history. However, when you look at the image in context with the images that proceeded it, this image combined all the other mechanisms of the previous images into one cohesive whole. This leads me to believe that Picabia saw de Zayas as the force which held their band of artists together and this image is paying homage to that.

"Dada smells of nothing, nothing, nothing.

It is like your hopes: nothing.

Like your paradise: nothing.

Like your idols: nothing.

Like your politicians: nothing.

Like your heroes: nothing.

Like your artists: nothing.

Like your religions: nothing".

We must all learn what art really is, learn to relieve it from the surrounding stupidities and from the passionate and useless admiration of the horde of false idolaters, as well as the money changers in the temple of success. Dada-ism offers the first joyous dogma I have encountered which has been, invented for the release and true freedom of art.

By subscribing to the doctrine that nothing was greater than anything else and tackling their issues with humor, I think the Dadaists and Francis Picabia were able to -- at least for a little while -- return to the pre-war joy of being an artist.