(Photo from The Crisis Supplement, July 1916)

I’m often naïve about how much else was going on during World War I beyond the war itself. It’s easy to look back and think that it was the only thing defining everyone’s lives for that four-year stretch.

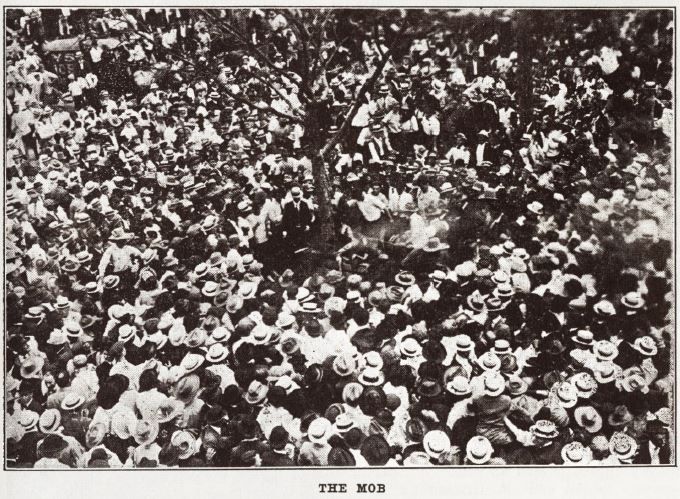

This was not so—for most people, I imagine, but especially for African Americans (and perhaps most Americans until 1917). Keene’s article sheds valuable light on the black campaign to use the war for political enfranchisement, finally getting their chance for equality. The NAACP’s modernist magazine, The Crisis, details much of this process. The June 1918 issue (the “Soldier’s Number”) highlights the various realities of wartime, including a passage about lynch law that particularly caught my attention. To gain more context, I found a supplement to the July 1916 issue that describes “The Waco Horror,” in which a young black man in Texas is brutally lynched and burned alive for killing a white woman. The piece retells the story in horrific detail while also providing general background about Waco, the political situation, and the town’s feeling in the aftermath of the event. His description of the lynching is not only disturbing in its specifics, but in its implications for the pervasive “blood lust” mentality present even beyond the actual “presence” of the war at the time (the total dehumanization of the black boy, the mob’s scramble for “souvenirs” after he’s dead). The reporter then closes the piece with larger assertions about “the lynching industry,” stating, “This is an account of one lynching. It is horrible, but it is matched in horror by scores of others in the last thirty years, and in its illegal, law defying, race-hating aspect, it is matched by 2842 other lynchings which have taken place between January 1, 1885, and June 1, 1916” (18). After providing a chart of how many lynchings have occurred each year in that time period (already 31 in 1916 after only five months), the writer implores, “What are we going to do about this record? The civilization of America is at stake. The sincerity of Christianity is challenged” (8). He pragmatically closes the article with the NAACP’s fundraising campaign to end lynching, a “crusade against this modern barbarism” (8).

The following year, America enters the war and the world changes, in some respects. Less than a year after the Waco Supplement, The Crisis quotes Attorney General Gregory saying, “For us to tolerate lynching is to do the same thing that we are condemning in the Germans. Lynch law is the most cowardly of crimes” (71). The New York Evening Post even equates lynching with “Prussianism” (71), expressing fear that the enemy could use examples of lynch law to turn black Americans away from their own country. The New York Post excerpt ends imploring Americans to “purge the country of this monstrous wrong” (71). Drawing from other editorials to marshal their evidence, the piece then quotes from the New York Evening Globe, which reminds readers that 222 lynchings occurred in 1917 alone as a testament to the insistence that “before these primary needs [education, right to work] comes the elementary need—…simple security of life and limb” (71). By insisting that “enforcement” (71-72) is the way to improve the lynching situation (talk about a euphemism on my part), the author takes a utilitarian approach unsurprising in the midst of total war. In wartime, as in all times, the major events of the day can be appropriated for larger political and cultural purposes. This idea has been particularly striking to me in how African Americans managed to defend their country not only as patriots but as human beings, valiantly fighting their way to equality in increasingly deeper senses of the term. And this focus on lynching provides a palpable illustration of the ways in which outdated ideas and practices become increasingly unacceptable in the emergence of a modern world.

Comments

Hannah Covington

Wed, 10/01/2014 - 13:51

Permalink

Casie, your post about the

Casie, your post about the lynch law made me go back and re-read the passage in July 18's issue of The Crisis. The photograph you put at the top of your blog reminded me of another snapshot I've seen of a lynching in the south where men have brought their wives, who are pictured around the hanging body with their picnic baskets, blankets, and children. It's a public event, a public spectacle, like a ballgame or city concert. Have you heard the song "Strange Fruit" (published in 1937) performed by Billie Holiday? It's grotesque and powerful, mostly because the grim reality is that lynchings continued well after WWI ended. Here are the lyrics:

"Strange Fruit"

Southern trees bear a strange fruit

Blood on the leaves and blood at the root

Black bodies swingin' in the Southern breeze

Strange fruit hangin' from the poplar trees

Pastoral scene of the gallant South

The bulgin' eyes and the twisted mouth

Scent of magnolias sweet and fresh

Then the sudden smell of burnin' flesh

Here is a fruit for the crows to pluck

For the rain to gather, for the wind to suck

For the sun to rot, for the tree to drop

Here is a strange and bitter crop

There are so many images at play in this song that I want to analyze on, but I also want to refer back to The Crisis article's comments on lynching. They shed light on another crucial historical implication of this sustained violence against African Americans in the South. Here's an important observation the author makes: "Every time a Negro is lynched there follows an unsettling exodus of Negroes to the North" (71). We now know this "exodus" as the Great Migration, which lasted from about 1910 until 1970. Between 1910 and 1930 alone, more than 1.6 million African Americans fled southern violence (among other things) and moved to the northeast, midwest, and west. This drastic southern diaspora changed the entire makeup and configuration of the African American population in the United States, prompting a switch from agricultural southern living to northern urban toil. Anyway, it's this migration is yet another unsettling effect (one The Crisis felt important enough to note even by 1918) of this unmitigated violence against African Americans.