The ways that Jake balances personal reflection with distance from the reader is really interesting. There is often a sense of restrain and deferral even as he lets us into his pain and alienation in brief moments.

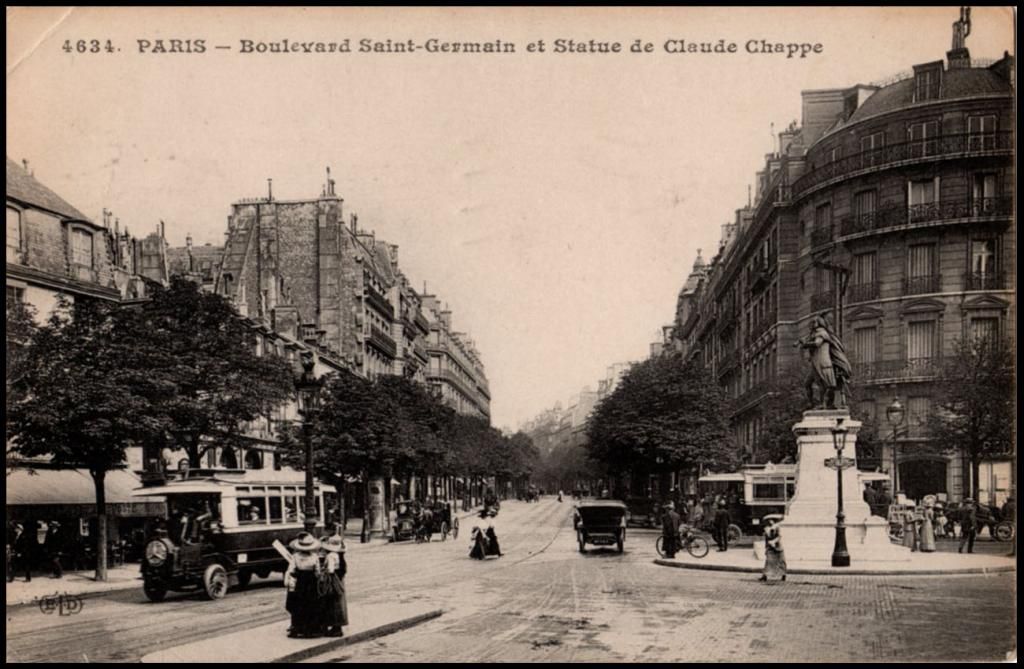

This tendency in Jake/Hemingway's narration stands out in a number of places, but particularly in one paragraph about the Boulevard Raspail in Chapter VI. Admittedly, at first I was just curious to know what "the semaphore" was (I'd never seen that word, much less connected it to its definition), but then grew more interested in Jake's reflections about "those dead places in a journey" (48). He vaguely alludes to "some association of ideas," but I don't get the impression that he's necessarily keeping the ideas secret from the reader so much as he's not sure he has access to those ideas himself. In this respect then, it seems like Jake is simultaneously restraining himself from showing too much to the reader and giving them a sense of his own experience--we can't get full access to his consciousness because on some level, he can't either.

Jake calls the street "ugly," but it doesn't seem like an entirely aesthetic judgment, then makes a distinction between "walking" and "riding" along--something I don't have much to say about yet, but it's interesting. Before we can get too close to Jake, though, he detaches himself by inserting a third-party text ("Perhaps I read something about it once"), then moves on to Cohn's "incapacity to enjoy Paris" (49). "Incapacity" is an important word, I think, because it implies both an actual lack of ability (disability) and a sort of mental block.

I hope I'm not reading too much into the text, but as I've been reading so far I've just found Jake's approach to storytelling to convey a lot of impressions of what it's like to keep working and loving in the wake of the war--a sense of boredom, but not a lack of humanity. Hemingway's stylistic choices in how he unfolds the story primarily through dialogue yet supplements them with Jake's scattered musings evokes the feeling that we are not only getting the chance to observe someone's postwar experience, but on some level to relive it ourselves.

(Image source: http://buttes-chaumont.blogspot.com/2012/02/semaphore-man.html)

Comments

Michael Dodd

Wed, 10/29/2014 - 10:38

Permalink

I’ve also been thinking about

I’ve also been thinking about Jake’s “humanity,” and it’s interesting that you contrast his humanity with his sense of boredom. I’ve been wondering if there may be a connection. For example, Jake seems to always be concerned with the way others are treated. He winces at Frances’s public belittlement of Robert Cohn (56), and at Brett’s insensitively “sending away” the count (“You can’t just like that”) (61), and he defends Harvey Stone to Cohn (51). Jake seems always to be trying to see the good in people even as he criticizes their faults (such as Cohn’s) (16).

Or is it that Jake is only enduring them out of boredom because he might as well be with them as with anyone else? And does he perhaps wince at poor treatment because he had seen enough of it in the war? I’m beginning to get the impression that all of Jake’s sorrows—stemming from his experience of war, his own injury, and his loss of Brett—are leading him to a revulsion of conflict coupled with an otherwise growing emotional distance from others. He doesn’t lack humanity, but he may have lost hope in humanity.