These magazines and journals are so fascinating, and it’s interesting to me that so many masculine topics related to worker strikes or labor would be taken up by women writers instead of men. On page 10 of The Masses issue Vol. 8, No. 12 (1916), there is a short sidebar simply title “Birth Control,” and it begins with the lede “The fight is not yet won by any means.” This column describes the charges and criminal trials against a Jessie Ashley and Ida Rauh for “giving away pamphlets containing scientific information about birth control.” The law deems the information as “obscene,” but whoever wrote the sidebar argues the law is “insane cruelty” and points out that “it is secretly defied by the governing classes before whose judicial representatives these ‘lawbreakers’ (Ashley and Rauh) will be solemnly brought to trial.” Why does this column not have a byline? Is it supposed to be assumed that it was written by a woman and does not need author credit? Or, was the sidebar such a risky piece to print that the writer’s name was not included to protect him or her? There’s a call to action at the beginning of the fourth paragraph: “You can help” by advertising the fight against the law. Readers don’t’ have to “risk their freedom,” but are encouraged to watch the trials of Ashley and Rauh, spread the word and attend the trails in person if possible. There’s even a small memo column below the text that could be filled out and sent to The Masses for updates on the birth control propaganda trial.

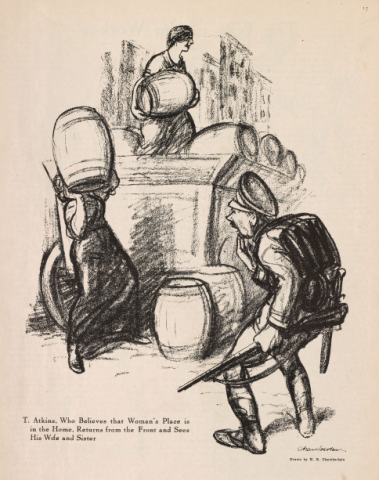

I know that this birth control topic does not directly relate to World War I, but it is included in an issue of The Masses that features many war images and articles such as “All Europe isn’t a Battlefield” and “San Francisco and the Bomb.” Birth control is one of the many ways women could fight for equality on the long road to suffrage — by having some say over their bodies and preventing pregnancy if they chose to do so. Two pages down from the birth control sidebar is a war-related sketch illustrating a surprised soldier coming home with his backpack and rifle to find women doing manual labor by loading barrels onto a wagon. The sketch is captioned “T. Atkins, Who Believes that Woman’s Place is in the Home, Returns from the Front and Sees His Wife and Sister.” This issue of The Masses is sending a message of if women are strong enough to do men’s work, then they are equal enough to make choices about their own bodies and practice birth control.