Jake as Jacob: Biblical Subtext in The Sun Also Rises

Submitted by Hannah Covington on Wed, 10/29/2014 - 11:05The first time readers meet Lady Brett is at a dance club, where she arrives with her entourage of jersey-clad young men. After turning down an already smitten Robert Cohn’s request for a dance, she makes what seems to be a rather off-hand remark, “‘I’ve promised to dance this with Jacob,’ she laughed. ‘You’ve a hell of a biblical name, Jake’” (30). In a study of Jacob “Jake” Barnes, I think it’s worth keeping the parallels between this WWI war veteran and his equally troubled Biblical counterpart in mind.

In Genesis, Jacob is born the weaker twin into a culture that valued physical strength, the ability to hunt, and earning the love of the patriarch (all qualities belonging to his brother Esau). Jacob, described as “content to stay at home among the tents” while his brother became a skillful hunter, captured his mother’s love (Gen. 25:27). By connecting Jacob with the domestic and maternal aspects of Hebrew culture, the story calls into question the nature of Jacob’s masculinity. He does not have his father’s love, so he must steal his brother’s birthright through cunning and trickery. An obvious parallel to Hemingway’s narrative is Jake’s similar fight to prove himself as a man even after he has been robbed of his masculinity by a war wound that renders him impotent. Just as Esau, the very symbol of virility and manliness is described as a “man of the open country,” so Jake retreats to the open country to partake in traditional masculine activities of fishing and hunting (Gen. 25:27). I would almost read Robert Cohn, who is presented so many times in contrast to Jake, as a kind of Esau in his brashness, brute power, and continual struggle to prove himself against Jake (in tennis, in writing, and in his pursuit of the same woman).

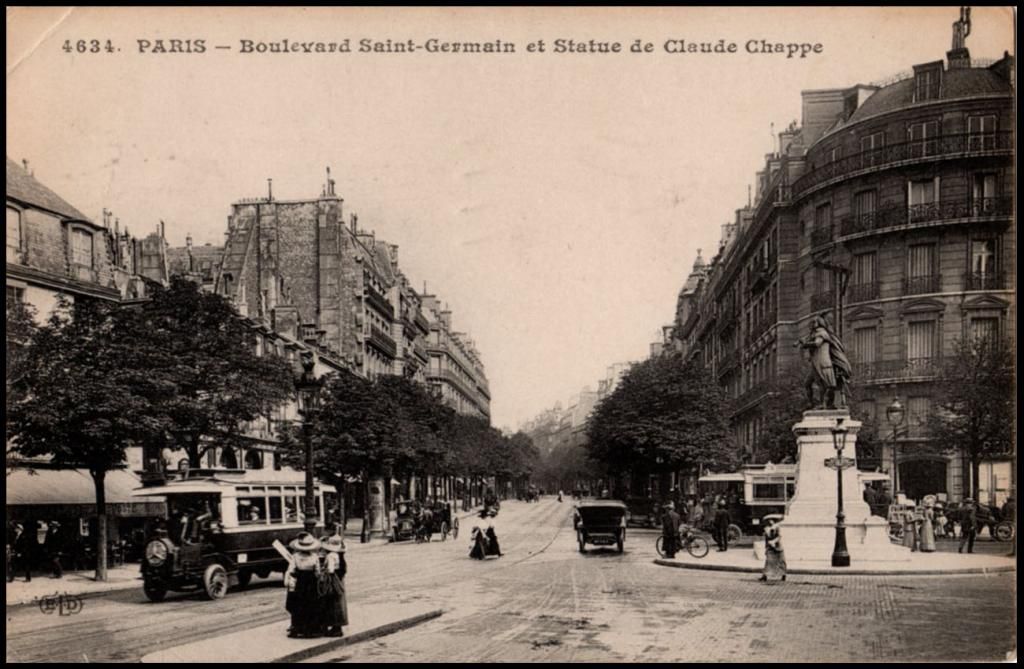

Like Jake, the Jacob of Genesis is also a nomad. He leaves his home country to dwell in a foreign land among strangers. Jake is an expat living on the Left Bank in Paris, and in many ways, he is also a vagrant. He moves aimlessly from café to café, country to country. Though he has lived in France for some time, he remains an outsider. Hints of his native, Midwestern industriousness and value for hard work come through in observations like, “All along people were going to work. It felt pleasant to be going to work” (43). Among his buddies, most of whom are writers and artists, it is Jake who stands out for his commitment to his newspaper job, sending off articles and news wires, and taking a sense of pleasure from it. Such is not the Parisian way of life. But still he lives there, an American roving about in Paris. Gertrude Stein in her book Paris France notes the tendency for artists to be nomadic when she observes, “…writers have to have two countries, the one where they belong and the one in which they live really. The second one is romantic, it is separate from themselves, it is not real but it is really there" (2). Jake really has three countries, counting Spain, but like Jacob in Genesis, he migrates upon the Earth without ever really pitching his tent permanently in any one place. And Paris, for him, does at times become unreal (more on that below).

Perhaps the most interesting connection to the biblical Jacob emerges in the Genesis narrative about Jacob’s wrestling with an angel. In his stubbornness and refusal to admit defeat, Jacob wrestles with this figure until daybreak, and when the angel realizes he cannot best Jacob, he cripples his hip instead. Even with this new—and permanent—injury, Jacob continues to wrestle, refusing to let go until the angel agrees to “bless” him. It is then that the angel tells Jacob that his name will be changed to Israel, for he has “struggled with God and with humans and have overcome” (Gen. 32:25). In The Sun Also Rises, we also see Jake wrestling. He fights against his inner demons, his similarly crippling experience in the war, and against his failed attempts to be with the woman he loves (also paralleling Jacob’s fruitless fight for Rachel). Jake also struggles with “God and with humans,” but Hemingway’s story is not a narrative overcoming; it is one of endurance.

Jake’s crisis of faith prompts him to take a sort of pilgrimage to Spain (he and Bill even talk with fellow train passengers about pilgrimages on their way to the Iberian peninsula). Paris is a world of the nighttime. Seedy café life, pulsing music, frantic dancing, and repeated descriptions of Paris being “dirty” (especially by Georgette) and “pestilential” (by Brett) make the déjà vu moments from each nights drunken stupor feel like some kind of PTSD episode, with Jake observing, “I had the feeling as in a nightmare of it all being something repeated, something I had been through and that now I must go through again” (70). So, like Jacob in Genesis, Jake packs up and moves on to Spain, which significantly first comes into view in the daytime. This day/night contrast solidifies Hemingway’s other prominent Biblical subtext in Ecclesiastes, where “the sun also ariseth, and the sun goeth down.” Spain is “bright” and “very clean” in ways that Paris is “dirty” (98). Once in Bayonne (which significantly straddles the border between France and Spain), Jake retreats into a Spanish style cathedral, praying for everything he can think of yet lamenting that he is a “rotten Catholic” (103). Still, he admires Catholicism as “a grand religion, and I only wished I felt religious,” ending his musings with the hopeful “maybe I would the next time” (103). Like Jacob, Jake wrestles with the angels and demons of his faith in both religion and in the meaning of life after a war, and though he emerges crippled, at least he can join his Hebrew counterpart in saying, “I saw God (or maybe the gods of war) face to face, yet my life was spared” (Gen. 32:30).