Earlier tonight I had to write an email to my dad consoling him about not landing a job that he had been hoping for. I know that this is a part of being a loving family member, and that it was not exactly a calamity that we were dealing with. But it is an uncomfortable position to be in; because I am so much younger than my father, because I have never had to provide for a family, because I lack experience with this particular kind of frustration, because I received the bad news in offhand fashion through a text message and have no idea of his precise feeling about it, because I need to optimistically reassure him regarding a future that I know nothing about, and must sound either naïve or callous in doing so because I spend so much time vocally fretting about my own occupational/financial future. My experience of what it means to love another person largely involves distress at their discomforts and disappointments combined paradoxically with a total insensitivity about confiding mine in them. I’m accustomed to my own anxieties, but totally freaked out by other people’s. The moment when a young man has to learn to comfort his father across the gulf of years and experiences and disappointments is always, I suppose, a difficult one.

All that stuff is the subtext to my terse, inadequate message to my dad, yet it would have felt unnatural for me to spell it out. But not, I would guess, for Vera Brittain in World War I. The tone of her letters to Roland is fascinating and utterly alien to me. We’ve discussed already the way that the invention of the telegraph, and the expectation of prompt replies, may have precipitated the tension which led to the development of the conflict, in much the way that the existence of text messaging gives rise to new social anxieties and misunderstandings. But most texts or emails that we send today are banal and say nothing, qualified as they are by the certainty that we can contact our loved ones and associates at any time. Metaphorically, the prime mode of correspondence has devolved from the letter to the postcard – the kind that says simply “Wish you were here,” with the unwritten reminder: “I still am.” Roland and Vera, in their letters, are charged with the urgent feeling that they must say everything. Yet this doesn’t necessarily make their communications profound, since they so often resort to the breathless clichés of love letter-writing that we expect from romantic novels. The possibility of Roland’s death, the delay between the sending and receiving of a letter, the passion into which war whips them, and their shared inundation in the literary realm, all contribute to give some of the letters, in my view, a quality of stately but empty ritualism: “I can only express the feeling that this deserted house gives me to-night by the world désolée—it was something less passive than depression and more active than loneliness…. I am trying to recall the warmth and strength of your hands as they held mine on the cliff at Lowestoft last night. So essentially You. It is all such a dream. Often as I have come home by the late train I have seen the moonlight shining over the mountains, but it has never looked quite the same as it did to-night…” (190-191). The French, evocation of nature, the ornate metaphors (“I feel as if someone had uprooted my heart to see how it was growing” p. 193), the recourse to “It is all such a dream…” We recognize this type of language. Comparing it to my own correspondences, my first instinct was to write about how the expediency of technology has decayed the passionate openness of war letters. But in fact, there’s something actually cold and impersonal about Vera’s letter as well; it is the language of courtship, not that of human interaction. And when Vera and Roland are together, their interaction is surprisingly awkward and troubled; without the buffer of print and post, the inexpressible, the murky complexities of emotion, become palpable and immediate. The peril of war and the distance – physical, verbal – that it creates between the two changes their relationship fundamentally. They become memories, ideals, archetypes described in other people’s poetry. Vera writes about “the grey and tragic present” (155), suggesting a pervasive deadness which typifies her age. And I’m put in mind of Nietzche, who said “That for which we find words is something already dead in our hearts. There is always a kind of contempt in the act of speaking.” The greatest speakers and writers have put the lie to this, but it seems to be sort of true for most of us mere mortals most of the time. The love between Vera and Roland, and the pain of their separation, must have lived fiercely in their hearts, but on the page it seems genericized. Their need to say everything proves as destructive to communication as is our modern custom of saying nothing. I think that their letters testify to the inadequacy of this form of communication to dealing with the reality of war. They suggest that there is a sense in which their own verbal expression has been “submerged” by “the high tide of war” (161); that the language of intimacy, of individualism, has been made another casualty.

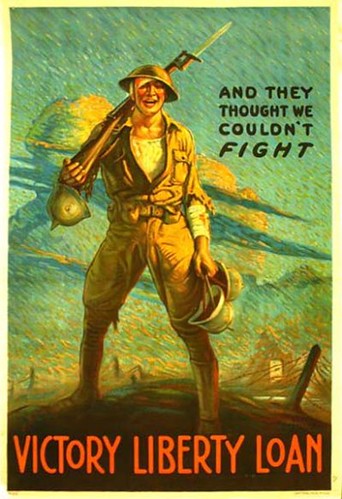

This poster appeals to a sense of adventure and victory. The man in the image is depicted as smiling triumphantly, holding several German helmets. This image is in the minds of many young men who want to enlist in the military, and plays to their emotions. It encourages them to join the war effort and prove that they can fight, and in a way prove their worth to whomever they think is watching. They want the glory of coming home with minor bandaged wounds, a smile on their face and the helmets of their enemies in their hands. According to this poster, after all, the worst that could have happened would be a scrape on the head or arm, with no permanent damage. In the world of this image, there are no amputations, no fatal head wounds, and everyone comes home smiling. It is a bright day in the image, possibly a sunset. This adds to the feeling of unreality and superiority, being illuminated as though on a pedestal. I think this kind of poster would have had a strong influence on independent people like Roland, who wanted to earn medals and be recognized as heroes.

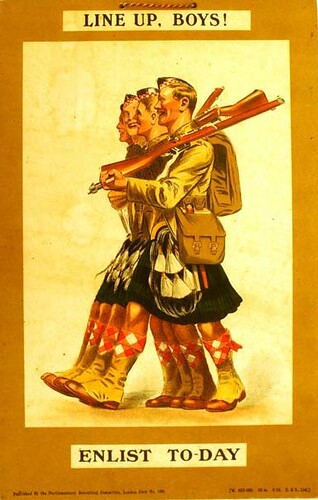

This poster appeals to a sense of adventure and victory. The man in the image is depicted as smiling triumphantly, holding several German helmets. This image is in the minds of many young men who want to enlist in the military, and plays to their emotions. It encourages them to join the war effort and prove that they can fight, and in a way prove their worth to whomever they think is watching. They want the glory of coming home with minor bandaged wounds, a smile on their face and the helmets of their enemies in their hands. According to this poster, after all, the worst that could have happened would be a scrape on the head or arm, with no permanent damage. In the world of this image, there are no amputations, no fatal head wounds, and everyone comes home smiling. It is a bright day in the image, possibly a sunset. This adds to the feeling of unreality and superiority, being illuminated as though on a pedestal. I think this kind of poster would have had a strong influence on independent people like Roland, who wanted to earn medals and be recognized as heroes. In this English poster, boys are encouraged to enlist for the war effort. The four boys depicted in the poster are all smiling, walking in perfect formation, and look like a big, 8-legged monster. Their bodies seem to blend together into a single conglomeration of uniforms. In contrast to certain posters, like those of Lord Kitchener, which point directly at the viewer, singling him out, this poster makes the viewer imagine himself as part of a unit of other boys just like himself. This takes away from the apprehension he might feel at enlisting by himself, because he will become part of a unit just as soon as he enlists. James writes that "Posters 'should be single, clear, specific' and 'must appeal to the emotions rather than to the intellect' (20). The image of all the enlisted boys walking happily side by side appeals directly to the 'emotions' of the viewer, turning the act of enlistment from a dreaded duty into a fun adventure.

In this English poster, boys are encouraged to enlist for the war effort. The four boys depicted in the poster are all smiling, walking in perfect formation, and look like a big, 8-legged monster. Their bodies seem to blend together into a single conglomeration of uniforms. In contrast to certain posters, like those of Lord Kitchener, which point directly at the viewer, singling him out, this poster makes the viewer imagine himself as part of a unit of other boys just like himself. This takes away from the apprehension he might feel at enlisting by himself, because he will become part of a unit just as soon as he enlists. James writes that "Posters 'should be single, clear, specific' and 'must appeal to the emotions rather than to the intellect' (20). The image of all the enlisted boys walking happily side by side appeals directly to the 'emotions' of the viewer, turning the act of enlistment from a dreaded duty into a fun adventure.