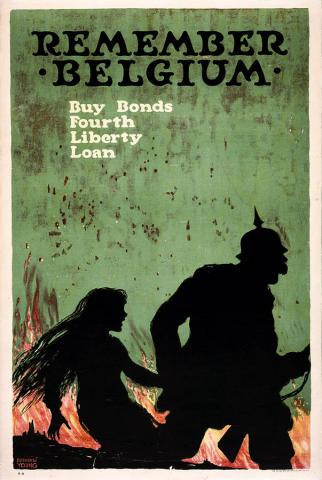

Distorting Memory in "Remember Belgium"

Submitted by Justin Stanley on Tue, 02/13/2018 - 09:52

While reading Pearl James’ “Introduction,” I was surprised at the level of agency WWI posters are given in mobilizing the home front. James suggests that “Through the viewing of posters, factory work, agricultural work, and domestic work, the consumption and conservation of goods, and various kinds of leisure all became emblematic of one’s national identity and one’s place within a collective effort to win the war” (James 2). James wishes to place posters within the larger cultural shift towards nationalism, or more appropriately as a driving factor. One of the more interesting pieces of evidence that I have found for the scholar’s argument is the poster “Remember Belgium,” in which Roland Marchand’s notion of “Zerrspeigel, a distorting mirror,” is used to produce and therefore affect memory in questionable ways (31).

The poster’s imagery bears most of the responsibility for this distorting effect, although it is the text that brings memory into play. Black silhouettes of a German soldier characterized by a spiked helmet dragging a significantly shorter, so perhaps younger, female prisoner in the foreground of a burning countryside. The sky above the flames is an interesting green and blue haze flecked with sparks from the flames. The same midnight black of the silhouettes is used for the text across the top of the poster, in a somewhat pre-modern type font, “Remember Belgium.” Finally, aligned slightly left and just below the title font, are the words “Buy Bonds Fourth Liberty Loan” in a striking white that nearly jumps out at the viewer when contrasted to the dark, drab color scheme of the poster as a whole. What is interesting about the poster is its paradoxical command that the viewer must remember, which of course is not the intent at all. The intent is to produce a memory, the memory of German soldiers burning and pillaging, suggestively capturing young women to imprison, torture, rape, kill, and whatever else the viewer can imagine. The command to remember itself gives credence to these suggestions, placing them in the definite past, and calling on the audience to access them as such. I would also argue that the image of a man dragging a woman can be so suggestive because of a sort of Freudian condensation, in which a single symbol may come to represent a combination of repressed themes. The selection of an image that so successfully demonizes the Germans in the hopes of inspiring the poster’s audience to feel obligated to buy war bonds is questionable, but in keeping with Marchand’s notion of the distorting mirror. What makes his metaphor so appropriate is the fact that a mirror is used to view the self, and what becomes distorted in viewing this obscene representation is, quite literally, our own subjectivities.