Introduction

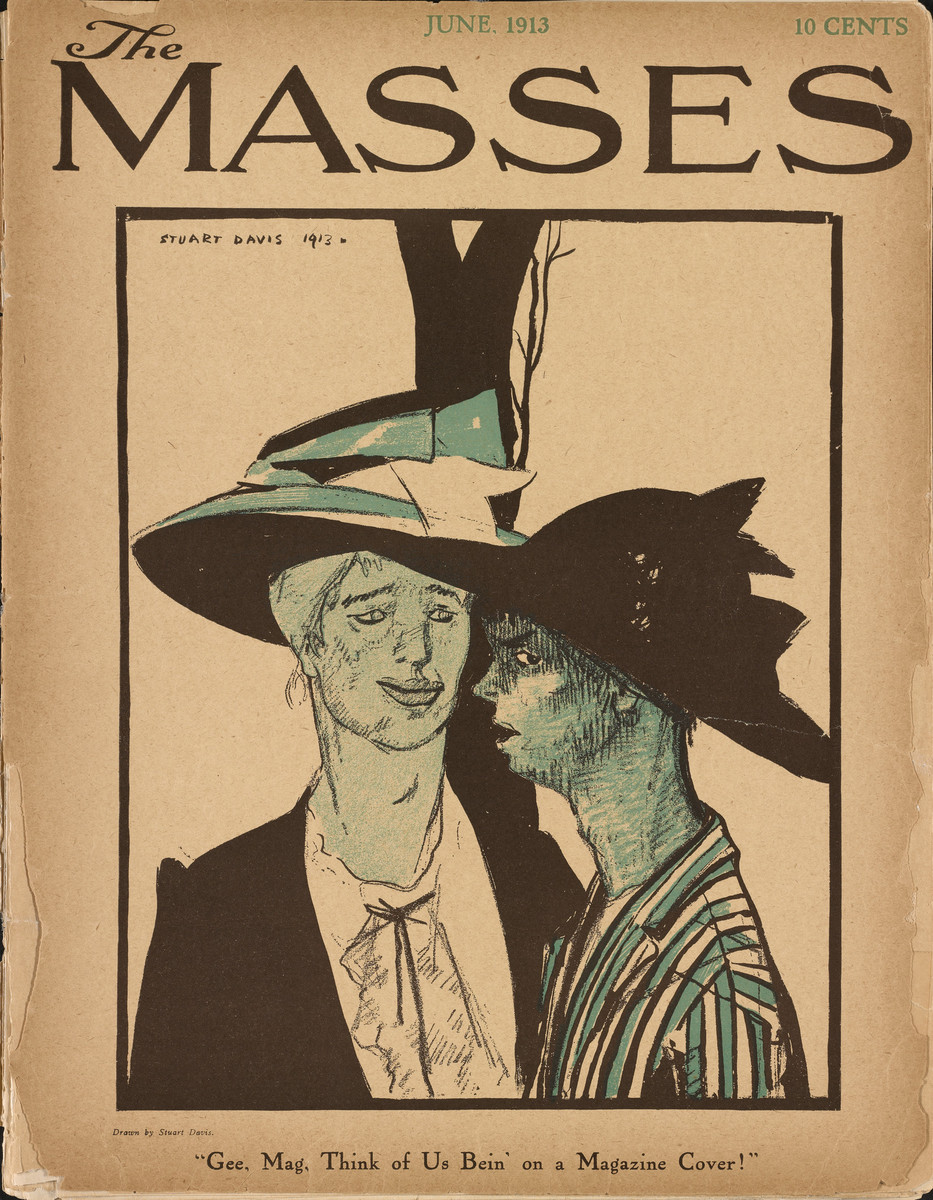

American women’s position in the first years of the 20th century was increasingly precarious. As the Suffragette movement gained momentum, the desire for increased attention given to women’s equality was matched by a sense of anxiety regarding women’s roles. In the cartoons, ads, and illustrations included in this exhibit, we can see how American magazines negotiated, interrogated, and responded to the question of woman’s role in the new century. In each displayed image, humor operates as a key modality through which these questions could be safely examined and anxieties discussed. In many instances, the cartoons reveal a sneaking suspicion of the overlooked power women possess. These cartoons weigh the implications of this power. “What if women,” these images seem to ask, “are actually more capable and competent than men?” Cosmopolitan’s “Votes for Wimmin”—a cartoon series depicting one man’s humorous turn from an opponent to a proponent of suffrage—playfully suggests the possibility of woman’s usurpation of the masculine role of protector. Likewise, The Masses’ “Adam & Eve” cartoon series suggests a comical rewriting of history in which the first woman becomes more powerful than her mate—but in an outlandish and grotesque way. In addition to the interrogation of women’s entry into a masculine realm, the magazines from this period also incorporate depictions of women’s “traditional” feminine power—that of her beauty, sexual appeal, and physical bewitchery. The exhibit includes images from The Masses, McClure’s, Cosmopolitan, and Scribner’s Magazine.

The images featured in this exhibit were culled from periodicals digitized by the Modernist Journals Project, a multi-faceted joint project of Brown University and the University of Tulsa. The project, which began in 1995, offers a range of English, Irish, and American periodical literature to augment studies of modernism and chart its trajectory in the English-speaking world. As a medium, magazines created a print network of debate and discourse that contributed to the rise of modernism. Important historical moments and cultural concerns—such as the anxieties surrounding women’s changing roles—are captured in the magazines. As scholars, we can examine these magazines to see how modernist and early 20th-century ideas developed “in real time,” so to speak. The images in this exhibit are also available for viewing in their original periodical contexts on the project’s website, modjourn.org.

Historical Context - Converging Movements

Traditional historical accounts of the American women’s suffrage movement locate its origin at the Seneca Falls Convention of 1848. Here, in Seneca Falls, New York, the first women’s rights convention brought together activists ready to organize and seek reform on a state-by-state basis. The momentum from this initial convention carried organizers through the Civil War (1861-1865) and brought some measure of success. By the turn of the century, women had successfully campaigned for full suffrage in four states: Wyoming, Utah, Colorado, and Idaho (Frost-Knappman and Cullen-DuPont 266). The intervening decades between these initial victories and the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920 brought mounting efforts to consolidate the various women’s groups and associations. In 1890, the National Woman Suffrage Association and the American Woman Suffrage Association--two of the largest suffrage groups--merged and remained unified until women nationally achieved the vote (Patterson 6). Through their demonstrations and increasingly public presence, these groups became common targets in print culture. Their members were often reduced to social types, and cartoonists used the suffrage organizations’ well-known acronyms as cultural shorthand for the broader feminist movement.

The increased visibility of women’s political participation in the early twentieth century coincided with the overlapping fight for women’s rights in the workplace. By 1900, one out of every five women had joined the workforce (Patterson 12). As growing numbers of women began working outside the home, labor organizations for working class women also increased. In 1909, for example, more than 20,000 women came together to form the Women’s Trade Union League and participated in what has commonly been referred to as the “first great strike of women” in the fight for better wages in the garment industry (13). Periodicals, especially socialist magazines like The Masses, used humor to address issues of labor as they related to women from a variety of economic classes.

The proliferation of educational opportunities for women at the turn of the century reinforced their growing autonomy both within and beyond the home. In 1900, more than 40,000 women enrolled in college, marking a drastic increase since the first woman graduate earned her college diploma in the 1840s (Frost-Knappman and Cullen-DuPont 266). Over the next few decades, college attendance among women tripled, and by 1910, about 40 percent of college students were women (Patterson 11).

The development of women’s movements also corresponded with and potentially inspired, as many scholars have deemed it, an early twentieth century masculine “crisis” in which the meaning of masculinity and ideal manhood shifted. The new image idealized the “valorization of muscular male bodies” and placed increasing value on men for their physical strength (Schreiber 21). The “ideal man” as he was presented in labor-focused magazines especially—such as the socialist-oriented The Masses, which many of our images come from—distinguished between the physical worker and the effete boss. In establishing the ideal worker as a man, such depictions minimized women’s growing presence in the workforce. When the magazines included cartoons focusing on women, and lower-class women in particular, their message was complicated. Despite the fixation on men as physically superior, many of the images we have included reveal an anxiety regarding even that gender assertion.

The debate over women’s evolving roles—in politics, the workforce, and the university—intersected with radical shifts in the broader print culture. The idea of the American “New Woman” gained currency in the late nineteenth-century press, and her image appeared in varying incarnations in periodicals during the first decades of the twentieth century. The various renditions of the New Woman were predominantly fashioned by male artists as they contested the shape that this image should take. Magazines, more than other printed materials, served as the textual site of these debates. In 1890, monthly magazines enjoyed a circulation of 18 million, and this circulation ballooned to 64 million by 1904, or, as Martha Patterson estimates, about four magazines per household (Patterson 2). Readers were therefore consuming a dispersed array of images. Ideal femininity, like masculinity, shifted during this period as the meaning of womanhood moved from the “true womanhood” of the domestic nineteenth century mother to the multi-faceted “New Woman,” a figure whose meaning varied based on the intention and perspective of those wielding the term (Schreiber 25). Rachel Schreiber asserts that “the visual culture of the magazine does not demonstrate cohesion—individual artists and authors approached the topics idiosyncratically, reiterating the varied meanings that gender can hold” (27).

The images culled for this exhibit reinforce Schreiber’s argument of the varied nature not only of expansive periodical print culture, but of the meaning of gender as well. Many of the cartoons included propose complicated and sometimes contradictory images as they reinforce the existing opinions that they simultaneously seek to undermine. While the “message” of the magazines remains incongruous and does not present one homogenous or unified mission statement, the collection of images reflects the uncertainty and confusion of not only the state of femininity in the early twentieth century, but larger questions regarding gender, politics, and the future of American culture.