As we close our time of exploring the particular experiences of a momentous and traumatic period in time—that is, the events surrounding WWI—I was captivated by the potential implications of the many moments scattered throughout To the Lighthouse which seem to be reflections upon the potential power and/or powerlessness of the human capacity for remembrance. Of course, the subject of To the Lighthouse is the fragmentation of a family and, by their association, a small community, but through this family Virginia Woolf simultaneously provides us with a poignant commentary on the repercussions of World War I.

I noticed last week Mrs. Ramsay’s intense desire to preserve moments in time, even in the face of persistent change. This was most apparent when, upon leaving the dinner, she turns in the doorway and, “With her foot on the threshold she waited a moment longer in a scene which was vanishing even as she looked” (111), as if to capture the impression forever in her memory. As we found in these next sections of the novel, however, her attempt is grimly futile, for we are told almost in a literal, bracketed “aside”, that Mrs. Ramsay “died rather suddenly the night before” (128), and further that Andrew Ramsay had died fighting in the war in France, and Prue, the beautiful daughter for whom Mrs. Ramsay was dreaming so beautifully at the dinner party, “died that summer in some illness connected with childbirth" (132). In result, Ramsay family does not visit the Isle of Skye for ten years, and time and decay begin to encroach on the memories of what has passed there.

Very soon we must confront the apparent futility of human striving and remembrance when the narrator asks: “What power could now prevent the fertility, the insensibility of nature?” and declares that “Mrs. McNab’s dream of a lady, of a child, of a plate of milk soup? It had wavered over the walls like a spot of sunlight and vanished” (138). This would seem to imply, or even declare, that we have no power whatsoever over the decay and death necessitated by the passage of time. And yet, Mrs. McNab does return, and does somehow slow “the corruption and the rot;” rescuing the house, as well as its collective memory, “from the pool of Time that was fast closing over them now a basin now a cupboard” (139).

In fact, reminiscing upon one’s (perhaps long buried) memories plays a significant role in the final sections of To The Lighthouse. Mrs. McNab continues to bask in her remembrances, thinking that “They lived well in those days. They had everything they wanted (glibly, jovially, with the tea hot in her, she unwound her ball of memories, sitting in the wicker arm-chair by the nursery fender” (140), such actions that Woolf refers to as “wantoning on with her memories” (140). The children, however, are still haunted by what has come before, and as Cam and James wind their way to the Lighthouse at last, James recalls the events we earlier saw of his childhood: “’It will rain,’ he remembered his father saying. ‘You won’t be able to go to the Lighthouse’” (186). Lily likewise sorts through the past as she paints on the lawn, and “she seemed to be sitting beside Mrs. Ramsay on the beach” (171). And to Mr. Carmichael she is almost compelled to ask: “‘D’you remember?’…thinking again of Mrs. Ramsey on the beach” (171).

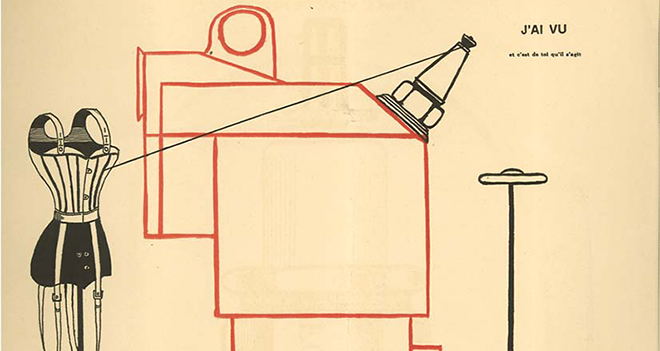

Lily, however, in contrast with James dwelling in his frustration, works through her memories in order to complete her painting, for she “was not inventing; she was only trying to smooth out something she had been given years ago folded up; something she had seen” (199). Indeed, this painting is apparently not significant for how it looks, but for what it shows about the process of Lily’s having painted it, and thus, perhaps, this same process reflects the anxieties present throughout the novel.

A neat conclusion to the remembered experiences of the Ramsay’s &co. is not provided by Woolf, but in attempting to work out what the potential lives of these people may be, I was repeatedly reminded of another bracketed aside:

“[Macalister’s boy took one of the fish and cut a square out of its side to bait his hook with. The mutilated body (it was alive still) was thrown back into the sea.]” (180)

In this description I cannot help but find a reflection upon the broken Ramsay family, reduced in number by three, and also those who have been left behind after the fragmentation caused by WWI. They are a family and a people emotionally damaged, even physically mutilated, and yet left alive. They have had no say in what has happened, their hopes have been betrayed, and far too much has been stolen away. Even still, they are alive, and so they must decide, each one, how it is that one may live. To do so must surely feel strange and stilted--ten years have passed for the Ramsay family, after all--or even unnatural after such turmoil. But perhaps it is the movement shown through the remembrance of tragedy that is most heartening, for it is, like Lily’s painting finished in a brief moment of clarity, an “attempt at something” (208).