Examining the shifting narrative from the first issue of BLAST to the second was the key fascination for me this week. Although what the magazine accomplishes for the print world is no doubt remarkable, I became primarily interested in the ways in which the Vorticists are fighting against the suggestion that something like “the war” could potentially disrupt the current movements in world of the arts. In both issues of BLAST there is the same desperate desire to set their art apart from the Cubists and Futurists (as well as utter disdain for the abhorrently naturalistic Impressionism, that takes its inspiration from the insipidly feminine curvatures of the natural world), but what I felt differently in this second issue was a fervent desire to maintain the momentum of Vorticism, apparently lest the movement fade away into obscurity (or even in fear of this potentiality, but perhaps this is only my reading into matters after the fact). In essence, Lewis & co. seek to assert that, although they are quite supportive of their nation, the war does not change in any way whatsoever the ways in which art is being reimagined and revolutionized in England; ie: even after the war concludes, Lewis & co. will still be those artistic “revolutionaries” in a new and vital movement. It should, perhaps, not seem so remarkable that hindsight would prove such a drastically different reality, but it is striking to me just how completely the assertions made, both here and in pre-war writings throughout our semester—I have in mind Brittain’s early letters, and the pre-war editions of The Crisis—are proven to be an underestimation of the great and lasting trauma of WWI. Understanding this, I know it is rather petty to feel that Lewis & co. are being, well, petty, to continue debating the truly great and wonderful difference between Vorticism and Futurism—and how both reject the terrible uncertainty of the natural world—in the midst of a terrible and nigh-worldwide catastrophe, but I suppose that one must continue their work in whatever way they see fit, even during times of crisis.

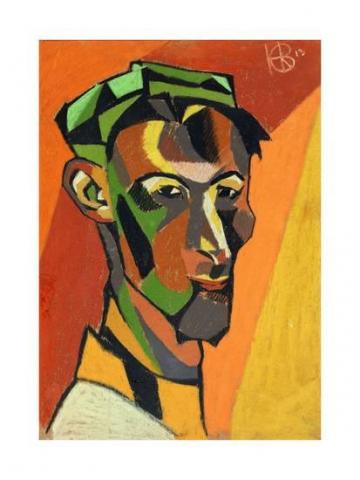

Nowhere was this struggle most apparent to me than in the section of the second issue of Blast, “Written from the Trenches” by Henri Guadier-Brzeska. Guadier-Brzeska was a French sculptor, one of the “Vorticists” who signed the initial manifesto, and was apparently quite involved in the initial movement, for according to the Modern Journal Project’s “BLAST: An Introduction,” he assisted in disrupting a meeting where the word “Vorticist” was mispronunced by “hissing ‘Vorti-cc-iste’ while the other Vorticists disrupted the event” (qtd. In Morrison). Even having read of his earlier exploits, however, I was still quite surprised by what he writes and sends while fighting during the war. When he declares in the second issue of Blast: “I HAVE BEEN FIGHTING FOR TWO MONTHS and I can now gauge the intensity of Life” (33), I imagined he would then describe the warfront for the reader, but instead the emphasis is placed upon his steadfast loyalty to the Vorticist philosophy, for “MY VIEWS ON SCULPTURE REMAIN ABSOLUTELY THE SAME” (33), and he even feels capable of suggesting that “THIS WAR IS A GREAT REMEDY” because “IN THE INDIVIDUAL IT KILLS ARROGANCE, SELF-ESTEEM, PRIDE” (33). A shocking proposal, indeed. Finally, I was quite surprised by his need to do an “experiment” in order to prove that the Vorticist ideals are still relevant, even during times of war:

“I have made an experiment. Two days ago I pinched from ran enemy a mauser rifle. Its heavy unwieldy shape swamped me with a powerful IMAGE of brutality.

I was in doubt for a long time whether it pleased or displeased me.

I found that I did not like it.

“I broke the butt off and with my knife I carved in it a design, through which I tried to express a gentler order of feeling, which I preferred.

BUT I WILL EMPHASIZE that MY DESIGN got its effect (just as the gun had) FROM A VERY SIMPLE COMPOSITION OF LINES AND PLANES” (34).

What are we to make of such insistence on the necessity of Vorticism when surrounded by the physical horrors of the war? Perhaps finding comfort in the precision of “lines and planes” may be a comfort in the midst of chaos? I am unsure, but although I understand each individual wartime experience may be vastly different, I am struck by just how dissimilar this account of the war-front is to many we have encountered previously. When I think of Vera Brittain’s adjustment to her contact with the natural (and somewhat grotesque, granted) human body in the various hospitals in which she worked, or Erich Maria Remarque’s descriptions of an entire troop of German soldiers returning to an almost return to Eden relationship with “mother” earth, I am captivated by the way in which some wartime experiences seem to strip away much of the desire to engage in civilized trivialities. Perhaps this only shows my own ignorance of the Vorticist ideals, but I would expect that, under such conditions one would cease to argue for any movement in particular. Indeed, a short notice located at the end of the piece brought home a sense of grim futility to me, for we are told on the very same page where this argument appears that “after months of fighting and two promotions for gallantry Henri Gaudier-Brzeska was killed in a charge at Neuville St. Vaast, on June 5th, 1915” (34).

Image of Gaudier-Brzeska's self-portrait found at: https://fineartamerica.com/featured/self-portrait-1913-henri-gaudier-brz...