Health, Nursing, and Propaganda in "The Crisis" 16.4

Submitted by Chelsea Mullins on Wed, 02/28/2018 - 08:31

While searching through various issues of "The Crisis" for content related to the War, I stumbled upon an article entitled "The Health and Morals of Colored Troops" from vol. 16 no. 4 that made me think more critically about the Keene chapter that we read for this week. Although Keene is dealing almost exclusively with poster propaganda, "The Health and Morals of Colored Troops" addresses all the ways in which the United States Army is attacking the problem of sexually transmitted infections and diseases that Keene also mentions in her chapter. As I read through this rather extensive list of actionable items (more STI/STD prevention than what is taught in many schools now), I found myself wondering why a captain in the medical division of the army would feel compelled to share this information with a larger audience than the soldiers the army is trying to protect. I found myself wondering if this was mean to allay public fears that sending your son off to the army might also mean that he loses not just his health, but his sense of moral rightness.

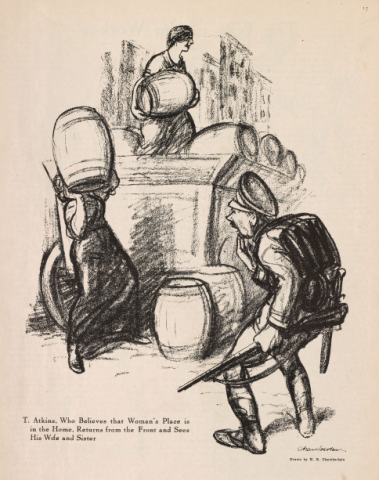

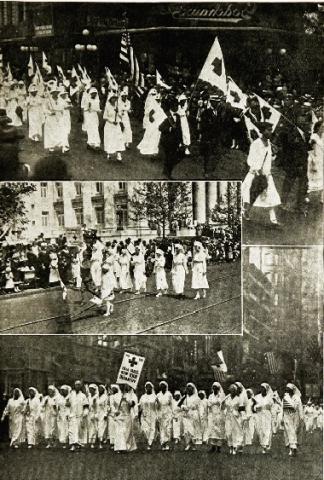

Complicating this narrative around health and morals is the fact that this article is immediately followed by three pictures of African American nurses marching in various cities throughout the United States. In almost every picture, the United States flag accompanies the Red Cross flag as the women march down a crowded road. Although there is no explicit call to action in these photos or even in their descriptions, I think they do hit on what Keene describes in her chapter as using visuals to draw a particular response from viewers. In this case, these picture show that African American women can also participate in the war effort outside of just conserving food. Considering that these pictures also follow a lengthy description of all the health services needed to be provided to African American soldiers, I could not help but think the placement of these photos as operating on at least an unconscious level which "The Crisis" readership may or may not recognize.