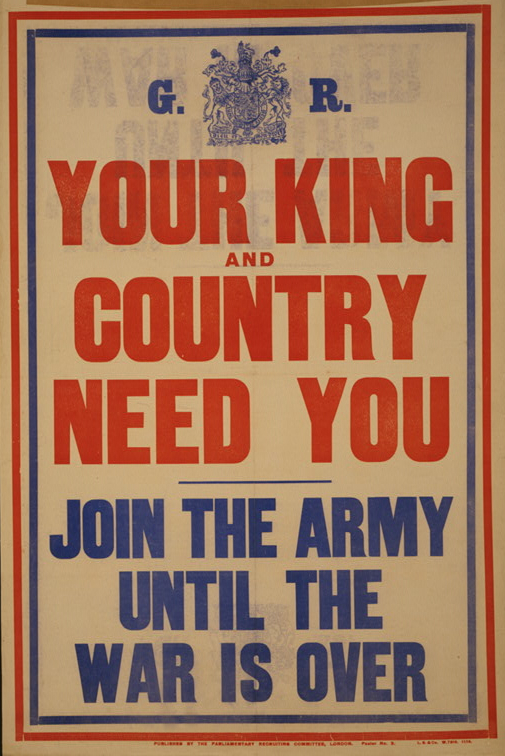

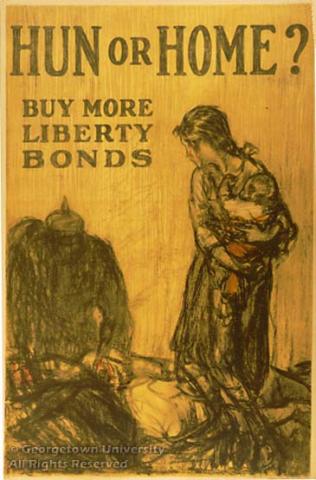

Considering my previous unfamiliarity with WWI posters, I’ve found Pearl James’ introduction on “Reading World War I Posters” to be quite a helpful starting point. I was especially interested to read of the pattern of wartime poster themes established by Maurice Rickards, which asserts that posters were “calling first for ‘men and money,’ they for help for the fighting man, then for ‘help for the wounded, orphans, and refugees,’ followed by calls for women workers, economy in consumption, and ‘austerity all the way around’” (qtd. In James 19). I found this distinction rather fascinating because nearly all of these categories may be easily found featured upon the McFarlin Library Special Collection Flickr page. One poster, for example, begs financial support for the war by depicting the man in a harrowing battle far away, exclaiming “Strike now! He’s fighting for you!” Another poster shows a scene of horror as a mother appeals for help while clasping a child to her chest, another child standing close beside her. This poster seems to mirror the consumers’ fears and nightmares while appealing for aid, which resounded with rumors of the German soldiers’ atrocities on the front lines (I am reminded of the German soldiers scoffing at the rumors of infant cannibalism in All Quiet on the Western Front). Still another poster—intending to persuade men to enlist—is inhabited by a group of joyful Scottish youths presented with the heading of “Line up, boys! Enlist to-day.” It is this final poster that I am chiefly interested in, because I simply could not help seeing in this imagined group of recruits—who are apparently either on their way to enlist, or soon to be deployed after having enlisted together—a possible reflection of the four young heroes of Vera Brittain’s tragic memoir, Testament of Youth, kilt-clad though the poster-youths may be.

In the poster we have a depiction of four handsome young men, gladly enlisting in order to participate in a just and noble war. “Line up, boys!” the poster exclaims across the top, with the concluding “Enlist to-day” along the bottom of the image. In this image am easily able to envision the proud and glad faces of Vera Brittain’s beloved Roland, Edward, Geoffrey, and Victor, as they initially contemplated the glorious deeds and experiences they hoped to attain through the war. Such idealism is fleeting, for it is only too soon before such hopes and dreams become utterly dashed by the cold realities of the numbing, senseless, mass-produced warfare of World War I. I feel an interesting claim resides in the particular words chosen for the poster, for they rather suggest that not only is enlisting the natural conclusion every young man must come to, but also that one will be in such great company—and with one’s own fellows, if the depiction of the four joyful youth laughing and smiling together as they proceed means anything—in the endeavor so as to necessitate forming a line in order to maintain order. The words perhaps even imply that one might be in competition with others of his own group to see who can enlist first. Although it is possible that this image sets the youths apart in depicting them as Scotsmen, it seems more likely intended to imply that each individual, regardless of his or her own background, must likewise make the right choice, and take part. As Pearl James notes, “many ritualized displays invited viewers to become participants in the scene depicted by the poster, and so to ratify or personalize its message” (9), and thus, in creating such personalized images posters essentially “redefined the boundaries of public space, bringing national imperatives into private or parochial settings” (James 10). Here, the war has been brought to the individual, and he or she is expected to respond.

Finally, Jennifer Keene determines that, regardless of the changing in rhetorical styles over the course of the war, posters “never departed from the storyline […] that portrayed the war as one in which individual soldiers could make a difference on the battlefield” (qtd. in James 33). It is just such an individual difference that the youthful Roland, Edward, Geoffrey, and Victor hoped to make, and yet in actuality the war was one in which a man such as Roland went “unadorned to his grave without taking part in a single important action” (ToY 287), in which Victor could die of a brain injury many weeks after attempting to reestablish his life, and in which Vera Brittain could only agonize over, not only the senseless death of her friend, but of “the superfluous torture of Victor’s long agony, the cruel waste of his brave efforts at vital readjustment” (ToY 358). Thus, wartime posters such as this cheerful encouragement to “Line up, boys!” and “Enlist to-day” undoubtedly supposes a joyful approach to the wartime conflict that is, in a way, rather lovely to behold. However, as Brittain’s Testament of Youth vividly illustrates, this hope had been based upon a patriotic ideal of heroic warfare that was very far, indeed, from the brutal realities of World War I.

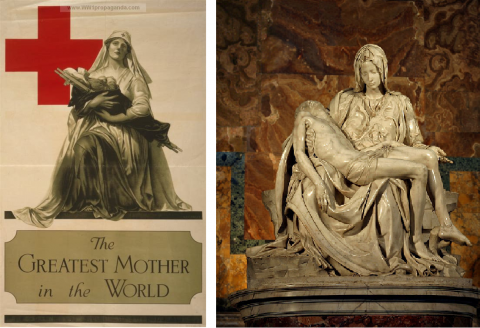

One of the things I found most interesting this week is the fact that in most of the posters that portray women, they are portrayed as people that care for others (nurses, cooks, mothers, etc.) and people that need protecting. Thus, the women are sending the men away in some of the posters to fight for them while they stay home and care for the house and family. In other posters, like this one, women are portrayed as nurses who care for the wounded men. Again, the women are the ones that are caring for others. In this poster, the language itself lends itself to thinking that women must be protected because instead of remembering the woman “behind the man behind the gun,” the poster asks the viewer to “remember the girl behind the man behind the gun.” This both places the woman as someone in need of protection and the woman as the one who is caring for the men. I find this interesting given that when men left their jobs to go to the war, the women had to take them so that 1) their families would have enough money to survive and 2) the men would have enough support at home from manufacturers and other businesses. In her article “‘The girl behind the man behind the gun': Women as Carers in Recruitment Posters of the First World War,” Angela Smith discusses another poster in which a woman is working as a munition worker. She is in the front of the poster, and the poster reads “On her their lives depend” (Smith 238). Again, instead of this poster showing that the woman is doing her part in the war and doing what is necessary, it puts the woman in the position of caring for the soldiers because she is the one that their lives depend on. Also, as Smith’s title suggests, the phrase “the girl behind the man behind the gun” was used on more posters than just this one. This phrase proliferates the idea that women are girls in need of protection and that they are the one’s solely caring for the men. This vision of women is propaganda because it makes the viewer feel better about the fact that women had to turn to working in factories and as munitions workers. Because the Victorian ideals of society have not yet lost their grip on society, these visions of women as needing protection and, as Angela Smith calls them, “carers,” makes society feel better about the work being done by women, as in "Remember the girl behind the man behind the gun."

One of the things I found most interesting this week is the fact that in most of the posters that portray women, they are portrayed as people that care for others (nurses, cooks, mothers, etc.) and people that need protecting. Thus, the women are sending the men away in some of the posters to fight for them while they stay home and care for the house and family. In other posters, like this one, women are portrayed as nurses who care for the wounded men. Again, the women are the ones that are caring for others. In this poster, the language itself lends itself to thinking that women must be protected because instead of remembering the woman “behind the man behind the gun,” the poster asks the viewer to “remember the girl behind the man behind the gun.” This both places the woman as someone in need of protection and the woman as the one who is caring for the men. I find this interesting given that when men left their jobs to go to the war, the women had to take them so that 1) their families would have enough money to survive and 2) the men would have enough support at home from manufacturers and other businesses. In her article “‘The girl behind the man behind the gun': Women as Carers in Recruitment Posters of the First World War,” Angela Smith discusses another poster in which a woman is working as a munition worker. She is in the front of the poster, and the poster reads “On her their lives depend” (Smith 238). Again, instead of this poster showing that the woman is doing her part in the war and doing what is necessary, it puts the woman in the position of caring for the soldiers because she is the one that their lives depend on. Also, as Smith’s title suggests, the phrase “the girl behind the man behind the gun” was used on more posters than just this one. This phrase proliferates the idea that women are girls in need of protection and that they are the one’s solely caring for the men. This vision of women is propaganda because it makes the viewer feel better about the fact that women had to turn to working in factories and as munitions workers. Because the Victorian ideals of society have not yet lost their grip on society, these visions of women as needing protection and, as Angela Smith calls them, “carers,” makes society feel better about the work being done by women, as in "Remember the girl behind the man behind the gun."